That pesky snowfall is actually good for the water supply

January 25, 2015As we find ourselves in the middle of a second snowstorm in just a few days, it’s as good a time as any to think about how much of that snow ends up in our drinking water.

Although snow can pile up quickly, an inch of snow and an inch of rain are very different in terms of quantity. For them to equal out in terms of liquid volume, it would take about 10 inches of snow to match the soaking that an inch of rain gives.

And while clearing off that snow can be a pain, it’s an important part of the water cycle. A mild winter with little snow leads to a greater possibility of a drought in the following summer. That’s due, in part, to the fact that the snow (and winter rain) doesn’t evaporate as quickly as water does in the heat of summer — meaning more of it sticks around to recharge the aquifer.

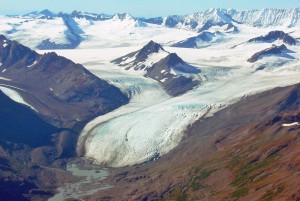

While it’s only a portion of the equation here, in other parts of the country and the world, it’s a major contributor to the water supply. For instance, the U.S. Geological Survey states that “As much as 75 percent of water supplies in the western states are derived from snowmelt.”

Snow trapped in the mountains acts as a natural reservoir for the western U.S., holding the water supply there until things warm up. All that snow eventually gets released into rivers. According to the U.S.G.S., “during certain times of the year water from snowmelt can be responsible for almost all of the stream flow in a river. An example is the South Platte River in Colorado and Nebraska.”

Like any reservoir, snow can harbor pollutants that will eventually find its way into drinking water. As the Penn State Cooperative Extension points out, “Anything that is put on the ground – oil, paint, chemicals, garbage – are termed non-point source pollutants and can be carried to rivers, streams or groundwater when the snow melts. Just because something is buried under the snow, doesn’t mean that it disappears.”

It’s something to think about when you’re shoveling out the driveway — and when you choose the type of product you’ll be using to melt ice and provide traction. Salt, the most commonly used de-icing product, poses a few problems:

- Salt residue blocks plants from absorbing moisture and nutrients.

- It can build up in soils, making them toxic (ever hear the term, “salt the earth?” It was a practice used to destroy farmland).

- Salt can leach heavy metals.

- Some salt products contain other chemicals. Sodium chloride (NaCL), for instance, may contain cyanide. Runoff from calcium chloride (CaCl) can increase algae growth in streams, as can potassium chloride.

If you must use salt, use it sparingly. If you can avoid it, try sand instead — or even a bag of all-natural, clay cat litter. These won’t melt the ice, but they can provide some grip. The down side is the mess they leave behind — especially cat litter, which can turn into a gray mud.